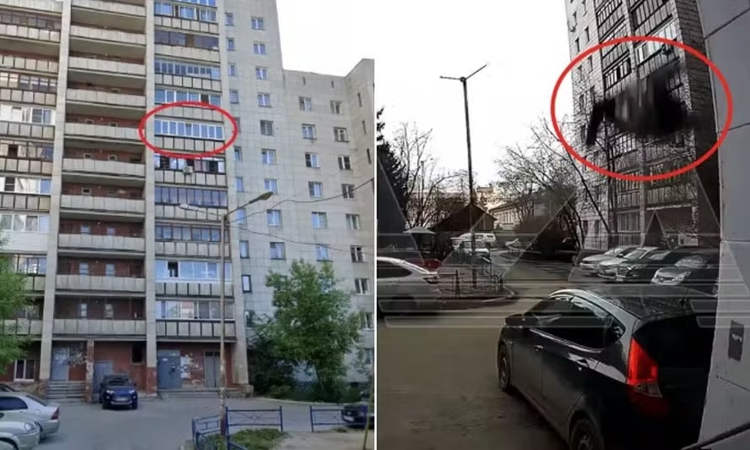

Netherlands-based startup SpaceLife Origin wants to send a pregnant woman 250 miles above the Earth to give birth to the first extraterrestrial baby in history, in the name of science.

Should our planet ever become unable to sustain human life, our species’ only hope would be to leave and settle elsewhere, be it a haven floating through space or another planet. But in order for this exodus to be a success, we first have to learn how to reproduce in space, and the founders of SpaceLife Origin want to get the ball rolling by sending a pregnant woman into space and having her give birth in zero gravity conditions. It sounds like a crazy idea, especially since humanity is a long way from becoming a spacefaring species, but SpaceLife Origin believes that our long-term survival depends on it.

Photo: qimono/Pixabay

According to Egbert Edelbroek, one of the executives of the Dutch startup, learning how to give birth in space is an insurance policy for the human race. Even if we ever discover or build an inhabitable place away from Earth, we must first uncover the secrets of space birth if we stand any chance of survival. To do that, SpaceLife Origin plans to organize a series of pioneering experiments over the next five years, with the most important one – an actual human birth in space – scheduled for 2024.

Edelbroek claims that he has already met with several spaceflight companies willing to transport the team 250 miles above the Earth, and with wealthy people willing to finance the experiment. He has also had discussions with women willing to become the first to give birth in space. However, even if SpaceLife Origin manages to find a volunteer, a commercial rocket and the money necessary to fund the whole thing, the mission is still bound to be a logistical disaster.

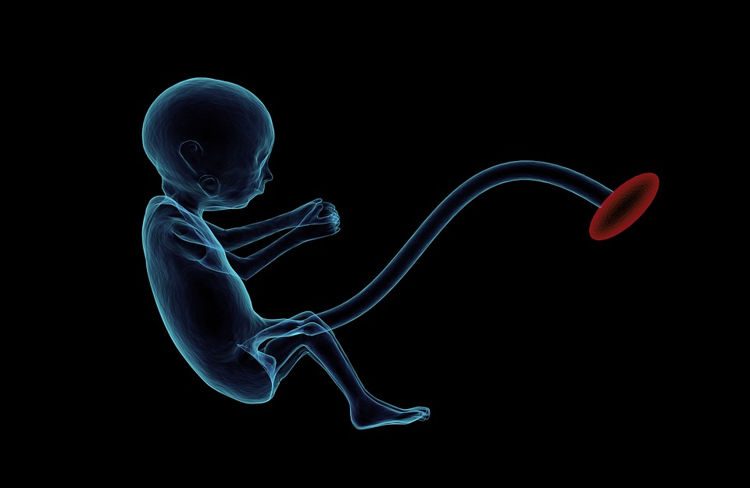

Getting the pregnant woman into space just before she’s ready to deliver the baby sounds difficult enough, but it’s the safety of the baby and the childbirth itself that experts are worried about. Astronauts usually experience three times the force of gravity during a rocket’s ascent to orbit, and in case of botched launches even triple that much, and no one knows how that will affect the fetus or the mother.

Photo: NASA-Imagery/Pixabay

Although we’ve never had a human birth in space before, we do have some experiments conducted on rats, fish, lizards and invertebrates. In the 1990s, rats gave birth on a U.S. space shuttle mission, and every pup was born with an underdeveloped vestibular system, the inner-ear structure that allows mammals to balance and orient themselves. They recovered their sense of balance shortly after, but the scientists concluded that infants need gravity.

The absence of gravity would pose serious problems, like the lack of assistance when the mother pushes the baby out, the difficulty of administering a pain-numbing epidural with the patient flowing through space, or bodily fluids floating through the shuttle as blobs.

Assuming that somehow everything goes right and the “trained, world-class medical team” accompanying the pregnant woman on her historical journey delivers the baby safely, there’s still the descent back to Earth to consider. These days, that means surviving a bone-rattling free fall through the atmosphere, followed by a parachute landing in some desert, not exactly the kind of experience a newborn and its mother should go through.

Photo: sbtlneet/Pixabay

And once the baby is safely back on Earth, what kind of birth certificate do you issue someone who was born in space?

SpaceLife Origin acknowledges that its plan still has many unknowns, but that’s the main reason for this pioneering mission, to find answers. Plus, some of the people involved in the project believe that if the company doesn’t do it, someone else will.

“I think at some point this will happen anyway, so we better do it in a very open and transparent manner. If it’s somebody working on his own, in isolation, not in contact with the rest of the world, you may discover that something happens and you can’t reverse it,” Gerrit-Jan Zwenne, one of SpaceLife Origin’s advisers, told The Atlantic.