The ripe berries of the genipa tree, called genipapo, have long been used throughout Central and South America to make syrups and liquors, but for a few years now unripe genipapo berries have become highly sought after for their ability to turn foods blue.

The coloring properties of unripe genipapo berries have been documented since the colonization of South America, when Europeans reported its use by local communities like the Tupinambás and the Pataxós as a temporary tattoo dye, but it wasn’t until 2014 that people learned about its potential to turn food blue as well. It was then that professor and biologist Valdely Kinupp published his book, Unconventional Food Plants in Brazil, where he detailed a process for extracting an edible blue pigment from genipapo berries. Natural blue pigments are very rare in the food industry, so Kinupp’s discovery caused quite a stir which eventually turned into a blue food craze.

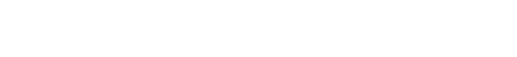

Photo: Hans/Pixabay

“The genipapo gained a fashionable status with the publication of the book,” Kinupp told Atlas Obscura. “Before that, hardly anyone talked about the fruit in the dining scene. It has become a trend, with blue bread, blue milk, blue pudding, and a multitude of bluish recipes.”

View this post on Instagram

But while the Brazilian biologist’s process for extracting an edible blue dye from unripe genipapo berries may have gotten people interested in the fruit’s coloring properties, it was a 2017 article by food writer Neide Rigo that really started the blue food craze. Kinupp’s extraction process yielded a blue so dark it almost looked black, but Rigo’s trial and error experiments with the natural dye resulted in a revolutionary discovery – genipin, the substance responsible for the blue coloration, gained a more vivid hue when it reacted to proteins and amino acids.

View this post on Instagram

“It was from there that many people started using the blue milk as a dye. It has opened a range of possibilities,” Rigo said.

View this post on Instagram

Milk was rich in proteins and amino acids, and was an ingredient in may dishes, which made it the perfect medium for mixing with genipin, and obtaining different shades of blue. Rigo’s recipes for foods like blue sauces, bread, pasta, cakes or tortillas gained a lot of attention online and inspired thousands to make their own blue foods and post them on sites like Instagram, where the hashtag #jenipapo yields thousands of results.

View this post on Instagram

Blue foods dyed with genipapo dye quickly attracted the attention of Brazilian chefs as well, many of whom used it to develop visually striking versions of famous desserts like îles flottantes, where the fluffy, white meringues float on a vivid blue sea of creme anglaise.

View this post on Instagram

“When I finished the dish, I realized the plating looked more like the sky and its clouds than the sea with a floating island, which made the dish even more beautiful,” chef Cesar Costa said about his unique îles flottantes. “Guests are petrified when they see the dish, it’s something pretty new for most of them”.

View this post on Instagram

The popularity of blue foods on Brazilian social media and in the country’s food industry is not very hard to explain. First of all, some of the genipin-dyed dishes are really striking to look at, but there is also the scarcity of truly blue natural, edible dyes. Anthocyanin comes to mind, but that gives food a purple color in most cases. You just don’t expect to see things like blue bread, or blue porridge, so they instantly draw attention.

View this post on Instagram