Chả rươi, or sand worm omelet, is a seasonal Vietnamese dish made with unsightly, two-inch-long sea worms that some say give the “delicacy” a caviar-like taste.

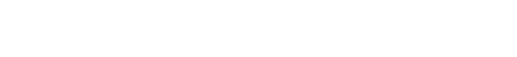

Every year, in late fall, street food stalls in northern Vietnam, particularly in Hanoi, serve a very special dish that looks very ordinary at first glance, but that actually contains a very peculiar ingredient. Chả rươi looks like a well-done egg dish mixed with various herbs, but owes its meaty texture and seafood taste to the ingredient that gives the treat its name – sand worms. Beaten egg, tangerine peel, onions, dill and spices, before the two-inch-long sea worms are added. The result is an ordinary-looking omelet with a very meaty kick that fans can’t get enough of in the months leading up to winter.

Photo: Khương Việt Hà/Wikimedia Commons

The “palolo” sand worm is not unique to Vietnam. It can be found along the coasts of many countries bordering the Pacific Ocean, including China, Japan, Indonesia or Samoa. In the latter, sand worms are fried and served with toast, baked into a loaf or even eaten alive. But why is it consumed for only one or two months out of a year? Well, it has to do with the sea creature’s mating habits.

Technically, only part of the palolo worm is harvested for consumption. Palolo sand worms reproduce by epitoky, a process in which the worms start growing specialized segments from the rear, which keep increasing until the worm can be clearly divided into two halves. These rear halves contain both eggs and sperm, and when its time to mate (usually during the ninth and tenth months of the lunar calendar), they break off from the worm and rise to the surface, forming large, slithering masses.

Photo: Viethavvh/Wikimedia Commons

The sand worms continue to live on the bottom of the ocean, and can experience epitoky several times a year. Because humans only harvest some these adrift reproductive segments, the sand worm population isn’t affected.

In centuries past, fishermen and farmers had no idea when the slithering masses of worms would rise up to the surface, so spotting them was a matter of luck. People would leap into the water and catch as many worms as possible using nets or their bare hands.

View this post on Instagram

Nowadays, however, farmers in Vietnam have started populating their lakes and paddy fields with the worms, as they can live in mud. When the worms rise up on specific days of the lunar calendar, they simply dry their lakes to harvest the precious ingredient. But because the sand worms have become a valuable resource in both Vietnam and China, farmers no longer consume them, preferring instead to sell them for profit.

Before being added to the chả rươi omelet, the sand worms have to be boiled to remove their tentacles and fishy smell. The latter is also combatted by the zesty tangerine peel and all the herbs. Still, the taste of sand worm can be too much for some people, so over time a less hardcore version of chả rươi emerged, one which contains more pork than worms. But for true chả rươi fans, the original, more expensive version is the only real option.

In the Vietnamese capital, Hanoi, cha ruoi is very popular this time of the year, and the smell of it fills the street, tempting some passers-by, and inducing a gag reflex in others.