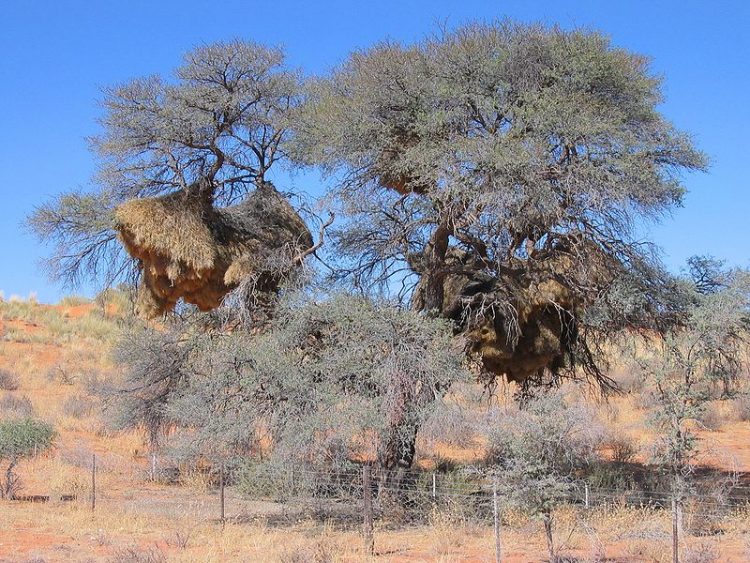

While most songbirds build small, discreet nests designed to shelter one clutch of eggs, the Social Weavers (Philetairus socius) of southern Africa build communal nests so large that they can pull down mature trees. Each structure can weigh over a ton, and range upwards of 20 feet wide and 10 feet tall, with over a hundred separate nesting chambers. Successive generations refurbish and reuse these compartments, often for more than a century.

Social Weavers utilize several different building materials, starting with a basic structure of woven twigs. They then line the interior with grasses and feathers and construct a 10-inch long, one-inch wide private entrance with downward pointing spiky straws to deter snakes. While a breeding pair will have a private apartment, most chambers house three or four of the birds at a time. The benefits of this lifestyle become clear in the context of the desert where temperatures vary dramatically.

Photo: Harald Süpfle/Wikimedia Commons

“I think the nighttime temperature was 30 or 35, and the temperature inside the chamber with three or four birds in it was 70 or 75 degrees Fahrenheit,” Gavin Leighton, a biologist at the University of Miami, told Wired Magazine. “So there’s this really huge thermal benefit to staying in these giant nests.”

The massive structure protects the birds not only from the temperature, but also from direct sunlight, rain, and drought. In many different animals, there is a high demand for water in the summer heat to aid in evaporative cooling, and most birds require lots of water to shed excess body heat by gular fluttering, a process which accelerates evaporative water loss. The Social Weavers, however, can retreat into their cool communal nest where they’re able to conserve water otherwise needed to dissipate heat.

Photo: Rui Ornelas/Flickr

Another benefit to living in these massive colonies is that it increases an individual’s chance of not getting caught by a predator. The chambers entrances are situated at the bottom of the structure, protecting residents from hawks and other predators. Other species have been known to take advantage of these benefits by squatting in the complexes. African vultures are known to hang out on the roof, and red-headed finches will raise families in empty chambers—as do pygmy falcons, birds of prey plenty capable of killing their landlords.

“It has been documented that pygmy falcons will sometimes eat social weavers,” said Leighton. “Which is kind of a depressing thought, because social weavers are building and maintaining this giant apartment complex, and then a predator moves in and starts eating them.”

Photo: Harald Süpfle/Wikimedia Commons

“But given that it is very rare for pygmy falcons to take sociable weavers,” he added, “it may be worth the risk to have them around if they intimidate not only snakes but potentially other bird species looking to squat in one of the nest chambers.”

Social weavers can fall victim to their success as well. While some nests can stand for centuries, others can get so waterlogged in the rainy season that the tree that supports them can collapse under the weight.

“And actually the nest I was working on, this most recent summer the entire tree just fell over,” said Leighton. “It ruined part of the nest, but some of the tree limbs that are still sticking out of the ground are supporting active chambers.”