‘Gympie-Gympie’ is hardly the name you’d expect for a stinging-tree. It looks quite harmless too, but in reality, the Gympie-Gympie is one of the most venomous plants in the world. Commonly found in the rainforest areas of north-eastern Australia, the Moluccas and Indonesia, it is known to grow up to one to two meters in height.

In fact, the Gympie-Gympie sting is so dangerous that it has been known to kill dogs, horses and humans alike. If you’re lucky enough to survive, you only feel excruciating pain that can last several months and reoccur for years. Even a dry specimen can inflict pain, almost a hundred years after being picked!

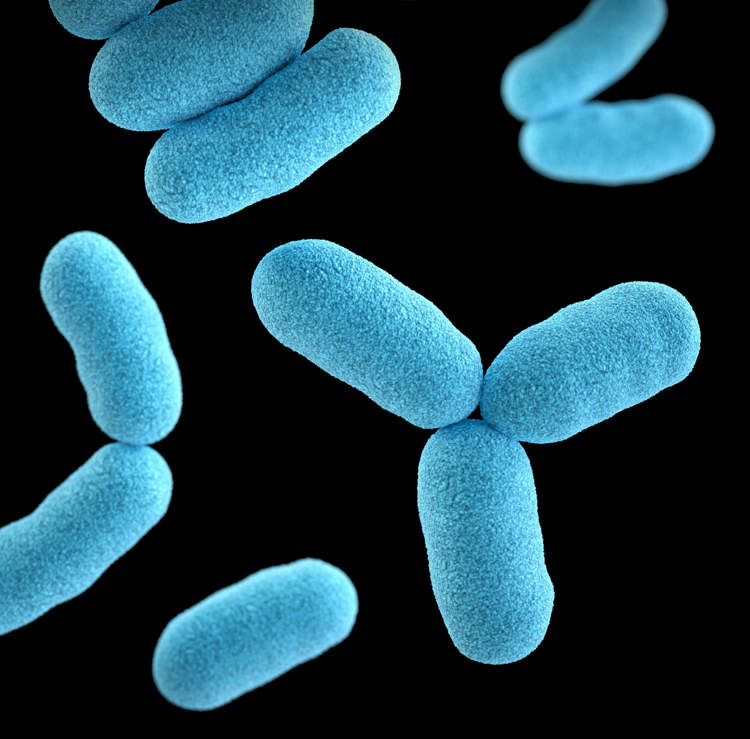

With the exception of its roots, every single part of the deadly tree – its heart shaped leaves, its stem and its pink/purple fruit – is covered with tiny stinging hairs shaped like hypodermic needles. You only need to lightly touch the plant to get stung, after which the hair penetrates the body and releases a painful toxin called moroidin. Sometimes, merely being in the presence of the plant and breathing the hair that it sheds into the air can cause itching, rashes, sneezing and terrible nosebleeds.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

According to virologist Dr. Mike Leahy, “The first thing you’ll feel is a really intense burning sensation and this grows over the next half hour, becoming more and more painful.”

“Shortly after this, your joints may ache, and you might get swelling under your armpits, which can be almost as painful as the original sting. In severe cases, this can lead to shock, and even death. And if you don’t remove all the hair (from your skin), they can keep releasing the torturous toxins for up to a year.”

Photo: DAHS AP Biology

The Gympie-Gympie serves as an unexpected hazard in rainforest clearings for foresters, surveyors and timber workers. Even scientists who are aware of the plant’s notoriety can sometimes become unsuspecting victims. That’s why most professionals do not venture out into such areas without respirators, thick gloves and anti-histamine tablets.

“Being stung is the worst kind of pain you can imagine – like being burnt with hot acid and electrocuted at the same time,” said entomologist and ecologist Marina Hurley, who was stung during the three years she spent in Queensland’s Atherton Tableland. She was a postgraduate student at James Cook University at the time, investigating the herbivores that eat stinging trees.

“The allergic reaction developed over time, causing extreme itching and huge hives that eventually required steroid treatment. At that point my doctor advised that I should have no further contact with the plant and I didn’t object.”

Photo: Dusty Miller

One of the first people to document the adverse effects of the Gympie-Gympie sting was North Queensland road surveyor A.C. Macmillan, who reported to his boss in 1866 that his packhorse was ‘stung, got mad, and died within two hours’. Local folklore is also filled with similar tales of horses in agony jumping off cliffs and forestry workers drinking copiously in order to dull the pain.

In 1994, Australian ex-serviceman Cyril Bromley described how he happened to fall into the tree during military training. He was subsequently strapped to a hospital bed for three weeks and administered all sorts of treatments that proved unsuccessful. He described it as the worst period of his life, when the pain made him ‘as mad as a cut snake’. He also told the story of an officer who shot himself after using a leaf for ‘toilet purposes’.

Photo: Australian Geographic

Most of the known cures for a Gympie-Gympie sting are rather rudimentary. Analgesics are usually prescribed for minor exposures to the plant. An innovative local remedy involves sticking a plaster or a hair waxing strip in order to rip all the toxic hairs away from the skin!

Interestingly, the British Army is believed to have displayed unusual interest in the properties of the Gympie-Gympie and its sinister applications in the late 1960s. The Chemical Defense Establishment at Porton Down (a top-secret laboratory that developed chemical weapons) contracted Alan Seawright in 1968, asking him to provide specimens of the stinging tree. Alan, who was then a Professor of Pathology at the University of Queensland, said: “Chemical warfare is their work, so I could only assume that they were investigating its potential as a biological weapon.”

“I never heard anything more, so I guess we’ll never know,” he added.

Sources: Australian Geographic, Bob in Oz, The Roving Apothecary